|

In the middle of the 18th century, the fallas were just one part of the events held to celebrate St Joseph's Day (19 March). During the morning of 18 March, rag dolls called peleles were strung across city streets from window to window, or small platforms were set up against walls displaying one or two figures (ninots) that referred to an event or to certain individuals that were particularly deserving of public derision. Throughout the day, children and young people collected objects to be burnt on bonfires called fallas. All were burnt the evening before St. Joseph's Day in the midst of much celebration. In the middle of the 18th century, the fallas were just one part of the events held to celebrate St Joseph's Day (19 March). During the morning of 18 March, rag dolls called peleles were strung across city streets from window to window, or small platforms were set up against walls displaying one or two figures (ninots) that referred to an event or to certain individuals that were particularly deserving of public derision. Throughout the day, children and young people collected objects to be burnt on bonfires called fallas. All were burnt the evening before St. Joseph's Day in the midst of much celebration.

The next day, devout Valencians and carpenters attended their local churches in honour of their patron saint. Families also celebrated the saint's day for anyone called José (also known as Pepe) with cakes, fritters and anisette. It was a time of widespread, neighbourly festivities.

The first documentation we have concerning the fallas is an official letter sent to the mayor of the city of Valencia prohibiting the placing of monuments (especially of a theatrical nature) in narrow streets close to facades. This measure adopted by the city's police for the purpose of fire prevention led the inhabitants to set up their fallas only in wide streets or at crossroads and in squares and, unexpectedly, led in the long term to an important transformation. Although the fallas continued to have a horizontal, theatrical structure made up of two parts (a platform and a scene arranged on it), they started to be placed on wheels so that they could be moved to the centre of a street or square. As they were no longer placed against a wall, the design changed to make it possible to view them from all sides. This created much greater freedom of construction and invited the inclusion of messages all round them.

For a long time, the term falla was used indistinctly for the torches, bonfires, rag dolls and platforms, but gradually the term came to be restricted to the satirical pyres that exposed vices or prejudices to public scorn. These fallas gave rise to great expectation and the local inhabitants came en masse to view them. The structure was usually prismatic and erected on a square, wooden base decorated with painted frames and canvases or panels to conceal the combustible materials underneath. The figures included in the scenes were usually dressed with old clothes. As with the popular theatrical performances of the miracles of St. Vincent, these satirical fallas usually came with verses that were hung on nearby walls or on the pedestals and that related to the subject of the falla. By the middle of the 19th century, these verses started to be printed and bound, giving rise to the booklet called the llibret. This made it possible to develop the subject much further.

The special characteristic of the satirical fallas is that they represent a reprehensible social action or attitude. They have a specific subject and aim to criticise or ridicule. They are more than mere bonfires or pyres because they show scenes referring to people, events or collective behaviour that their makers - the falleros - consider should be criticised or corrected. The two most popular subjects for falleros in the 1850s were eroticism and social criticism. The special characteristic of the satirical fallas is that they represent a reprehensible social action or attitude. They have a specific subject and aim to criticise or ridicule. They are more than mere bonfires or pyres because they show scenes referring to people, events or collective behaviour that their makers - the falleros - consider should be criticised or corrected. The two most popular subjects for falleros in the 1850s were eroticism and social criticism.

In 1858, the falleros in the Plaza del Teatro were officially prohibited from erecting a moving falla with a direct allusion to social inequality with verses written by Josep María Bonilla, but they went ahead all the same the following year. The press gave the name of "erotic falla" or "anti-conjugal tendency" to the many fallas that alluded to racy or risqué subjects with verses using double-entendres that reflected a hedonistic, lewd mentality. Bernat i Baldiví wrote llibrets on such subjects but the best-known is that written by Blai Bellver for the falla in the Plaza de la Trinidad in Xativa in 1866. This was called "The Cross of Marriage" and was severely condemned by the Archbishop.

Throughout the 19th century, the Town Council and the authorities in general tended to disapprove of these fallas. Their policy of repression, which aimed to modernise and civilise the city's customs by eradicating popular celebrations such as the Carnival and the Fallas, was applied with rigour during the 1860s when heavy taxes were levied on permits for setting up fallas or playing music. This led to a reaction in defence of local traditions and, in 1887, the magazine La Traca awarded prizes to the best fallas. The initiative was continued by an association called Lo Rat Penat. This explicit support from civil society provoked competitiveness amongst the different neighbours' committees, stimulating fervour for the fallas and encouraging artistic creation. Criticism did not disappear from the subjects of the fallas (in some cases, it was politically radical) but a new trend arose favouring formal structural and aesthetic concerns. Throughout the 19th century, the Town Council and the authorities in general tended to disapprove of these fallas. Their policy of repression, which aimed to modernise and civilise the city's customs by eradicating popular celebrations such as the Carnival and the Fallas, was applied with rigour during the 1860s when heavy taxes were levied on permits for setting up fallas or playing music. This led to a reaction in defence of local traditions and, in 1887, the magazine La Traca awarded prizes to the best fallas. The initiative was continued by an association called Lo Rat Penat. This explicit support from civil society provoked competitiveness amongst the different neighbours' committees, stimulating fervour for the fallas and encouraging artistic creation. Criticism did not disappear from the subjects of the fallas (in some cases, it was politically radical) but a new trend arose favouring formal structural and aesthetic concerns.

Eventually, though rather reluctantly, the City Council of Valencia took over from Lo Rat Penat and awarded the first municipal awards for the fallas at the end of the festivities - one for 100 pesetas, and another for 50 pesetas. The social climate was not only in favour of this initiative but demanded it. A wide range of organisations was involved - cultural, recreational, civic, sporting, political and for workers - and all of these helped to promote the fallas during the first decade of the century. In return, the fallas increasingly devoted their attention to exalting local values, resulting in a growing association between the festivities and Valencia as their centre. From the start of the 20th century, the fallas no longer maintained the dual structure of platform and scene. A new concept took over in which the figures were no longer the most important part. The fallas now basically comprised three different elements - a low base with various platforms for the different scenes, a central body holding up the monument and a top.

The latter usually comprised a large, allegorical figure, condensing the topic of the whole falla and summarising the scenes below it. The latter usually comprised a large, allegorical figure, condensing the topic of the whole falla and summarising the scenes below it.

The falla did not only contain a scene set against a background but content was expressed in the whole of the sculpture and had to be deciphered by walking all round the falla looking at it from top to bottom. Fallas had become lavish, majestic and imposing - large enough to be seen from a distance. The competitiveness introduced by the awards meant that the artists strove to produce monumental, elaborate creations.

In 1927, the Valencia Atracción association for the promotion of tourism organised the first Falla Train to bring emigrants from Valencia living in other Spanish provinces back to their home town for the festivities. This was so successful that Valencian society became even more devoted to its fallas and the number of monuments constructed grew and grew. The festivities soon came to require better organisation. The General Association for the Valencian Fallas and the Central Fallas Committee were created to represent the commissions and to organise the celebrations.

An article published in 1935 by Y. Llopis Piquer and entitled "How the fallas are prepared" describes the production of a falla in detail.

"The most important elements are: cardboard, plaster and wax, without forgetting the wood of the frames and the metal mesh covered with sacking for the large figures."

Using these simple materials, the Valencian artists emulate the large, long-lasting creations of sculptors, showing their skill in the production of grandiose monuments.

The most difficult and complex task is the construction of moulds for the heads. These are based on clay models which are then cast in plaster and subsequently in wax to give heads that are then completed by adding a moustache, a squint or a sneering expression to give a non-human touch and turn them into the characters featured in the falla.

The bodies are easier to build. The cardboard is pressed while wet onto plaster moulds and then shaped, an essential skill for any up-and-coming falla artist. And a further clay mould is made resulting in yet another human incarnation which will then be completed with physical distortions and material additions. This is the basic method used for turning out the multiple characters of the fallas. The bodies are easier to build. The cardboard is pressed while wet onto plaster moulds and then shaped, an essential skill for any up-and-coming falla artist. And a further clay mould is made resulting in yet another human incarnation which will then be completed with physical distortions and material additions. This is the basic method used for turning out the multiple characters of the fallas.

The most difficult part is to paint the wax. There are few artists who are capable of injecting life into the figures by the use of colour but, by dint of experience and perseverance, miracles take place. What still remains to be done? The bodies are then placed on a wooden strut which serves to attach lightweight materials such as straw, cloth, sawdust and wax. The figures are finally erected on the actual day of the plantá when the fallas are placed in their final locations and the frames and mouldings are hammered on. Once in the streets, the figures blend with city life and, in the night-time darkness, observers can be forgiven for not being able to distinguish between what is real and what is fantastic.

Texts: Antonio Ariño

JUNTA CENTRAL FALLERA

COMMUNICATIONS MEDIA DELEGATION

Las Fallas

(15 - 16 - 17 - 18 & 19 March)

The Fallas festivities are the expression of a unique kind of art using large wooden structures covered with painted papier-mâché. Recently, however, other materials are also coming into use.

This festival is also a satirical and ironic vision of local, provincial, national and even international problems and themes.

The Fallas criticize almost everything and everyone imaginable, although they do so with tongue in cheek. Over 370 full-scale fallas and 368 children’s fallas are mounted throughout the city, and some of these reach extravagant heights, although they do not usually exceed 20 metres.

Each falla elects their own Fallas Queen from among the Fallas maidens who form the court of honour of that particular Falla. Towards the end of the year, they present one of these lovely ladies - not necessarily their Fallas Queen - to the competition from which the judges will chose the thirteen Valencian women who will make up the court of honour of the main Fallas Queen of the entire city of Valencia. Children’s fallas follow the same process.

For many years, the Fallas Queen of Valencia was chosen by the Mayor, who was the honourary president of the Central Fallas Committee called the "Junta Central Fallera", responsible for coordinating all of the Fallas commissions. For this reason, the election of the Queen would often correspond to women belonging to the most representative families of the city. Thus the Fallas Queen roster contained many illustrious surnames such as Franco, Suarez, Fernández de Córdoba, and others.

In 1961 this process changed when Lolita Alfonso Sánchez, an orphan from the House of Goodwill, became the Valencia Children’s Fallas Queen. This marked a new starting point for the selection of Fallas Queens among Valencians.

Today, the election of the Fallas Queens of Valencia is governed by democratic vote among the candidates being presented.

The nominees public presentation, which follows their proclamation by the Mayor in the Chamber of the City Hall, is a solemn event in which all Fallas commissions and much of Valencian society take part. The ceremony was held for many years in the "Teatro Principal" (main theatre) of the town, but today the Palau de la Música (or the Music Auditorium) has taken over as the annual venue because of its larger capacity.

Fallas is the culmination of the work and efforts of an entire year. The whole city mobilizes itself and contributes to the Fallas, which also enjoy the institutional support of the City Council. The authorities set up their own falla and help to give the festivity an exceptionally attractive air.

It is no exaggeration to say that almost every street corner has its own falla and fallas commission. During the festivities, Valencian women wear their best traditional clothes and parade through the streets in colourful pageantry under their fallas standards to the sound of regional music.

At midday, each falla stages its own sound fireworks display, harmonizing the booming sounds of rockets with the smell of gunpowder.

At night there are spectacular fireworks displays that brighten up the nighttime sky.

In the Fallas casales (places where fallas celebrators gather) there is no time for sleep. It is fiesta time for five whole days.

The flower offering to the patron saint of Valencia, Our Lady of the Forsaken, is staged on two consecutive days. Thousands and thousands of flowers are placed over a wooden structure that serves as the framework upon which her image is formed. This is located in front of the Basilica and the entire Plaza is perfumed with the fragrance of endless bouquets of flowers.

Almost 100,000 Valencians take part in the procession. And of course, every day at five o´clock in the afternoon there is an important bullfight within the framework of the March Bullfighting Fair.

On the night of the 19th, Valencians burn down their creations, saving only what is known as the "Ninot Indultat", or the “reprieved figurine”, which becomes a museum piece. The children’s fallas are burnt at ten in the evening, with the exception of the first prize in the children’s category, which is set alight at ten thirty, and the city council children’s falla, which goes up in flames at eleven.

At twelve o’clock midnight, preceded by a grand fireworks display, the large fallas are set to the torch.

The entire city is filled with flaming fallas. At twelve thirty the first prize Falla is burnt and at one o´clock at night the Falla in the Plaza del Ayuntamiento is set alight, symbolically finishing for another whole year this semi-pagan, semi-patriotic, semi-religious fiesta that stirs the hearts of the Valencians.

On the day after the ‘night of fire’, a few marks on the asphalt is all that remains of the falla that stood so proudly the night before. On this very same day, the next fallas campaign gets under way.

The fallas fiesta was born in Valencia and quickly spread to other towns in the region, even outside the immediate area.

As a traditional Valencian festival, it is in the capital city Valencia where the Fallas command the most colour, participation and their greatest impact.

From the end of February, Valencia starts its fiestas with the so-called ‘Crida’, which is the call to action, followed by the Ninot Parade, the splendid Parade of the Kingdom, the "Song of the Kindling Wood" and the Ninot or figurine exhibition.

As for the origins of the Fallas, they seem to be connected with the pagan celebration of the spring equinox. It is said that in olden days craftsmen toiling throughout the wintertime would extend their working hours by using a light perched on a stand which they called a ‘parot’, something like a large candelabrum with various arms or wooden appendages. When spring came, they would celebrate the lengthening of the days that made their ‘parot’s superfluous by taking them out of doors and burning them in the street on the eve of St Joseph’s day. Logically, this custom was initiated by the carpenters of the city.

Today we know that since 1497 carpenters have been celebrating this Patron Saint’s day with a feast. There is a curious document still preserved from the 15th century which refers to “the day on which the joiners burn the pole.” Later on, the stand was adorned with old garments, much like a scarecrow, and was burnt in a bonfire along with odds and ends and leftovers from the workshop. After this, the stand was given a human visage intended to mock a well-known personality in the neighbourhood. Thus the Ninot, or doll-like effigy, was born. It soon became a fundamental element in the Fallas feast, no longer used on its own, but accompanied by a whole pageantry of figures.

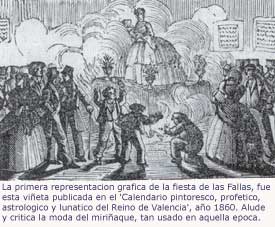

Another important advance was made with the appearance of the “subject” or “theme” of the Falla, generally something satirical or critical, expressed in humorous verse, although perhaps bearing on historical fact or some aspect of local life. These rudimentary representations gave birth to the ‘llibret’ or explanatory book written in the Valencian vernacular. After propping the figurines on full-scale pedestals in the 18th century, the creation of the Fallas festival was almost complete.

The name of the ‘fallas’ was not originally given to the figurines or to the entire monument itself, but rather to the fire which was supposed to consume the whole construction. The scholar Carreres i Zacarés discovered a quote on the fallas dedicated to San Vicente: in 1596 one Pedro Toralba was paid the sum of 74 pounds, one shilling and 6 pence for the possible use of his grills on which he burnt “the fallas which are made on the feast day of the Glorious Saint Vicente Ferrer.”

The fallas dedicated to St Joseph quickly obtained the overall applause of the modest working neighbourhood, but was snubbed by the upper class, and the more puritanical. Thus, the journalist José Ombuena in his book on “The Fallas of Valencia” took note of a complaint made by a devout Christian. This reproof appeared in the “Newspaper of Valencia” in 1792, and included the answer given by the same periodical to a certain vexed priest called Traggia: “Sufficient reason you have as the good Christian you are to be full of sorrow when you observe our streets and plazas full of pyres and figurines all ridiculously dressed, entertaining the great majority of the populace, who on days such as these fully forget their obligations and lose much of their otherwise productive workdays.” Not many years later, in 1808, the Frenchman Alexandre de Laborde became acquainted with the Fallas of Valencia and described them in his book “Itineraire descriptif de la Espagne” in the following manner: “Every year on the 18th of March, the eve of St. Joseph’s Day, cabinetmakers and carpenters come out onto the streets, each in front of his own workshop, to build truly theatrical representations of life-size figurines, covered with the clothes of the character they wish to represent. They are built with very light wooden structures, a mask forms their faces, their clothes, headdress and adornments are of paper - quite often done with great ability. These figurines are set up on a huge pyre which is usually well hidden, and surrounded up to its full height by a thicket of mock adornments all artistically positioned.” He also mentions that fine sights could be seen: “at nightfall these figurines were set alight, and in an instant the entire representation goes up in flames. These representations are called the Fallas de San José...” The importance of the feast was described as follows: “People press thick against one another, persons of a higher position mingle with the masses; people come from miles around and forget all they may have on their minds however important their affairs may be.” It seems that fallas were adorned in those days with all kinds of erotic paraphernalia, with much symbolism using the shapes of fruits and vegetables, in addition to extending criticisms of all their neighbours and the town authorities.

Perhaps this was the reason why the Fallas were outlawed in 1851 by the Mayor of Valencia, the Baron of Santa Barbara. In 1883 the City Council stamped a tax of 30 pesetas per falla on the festivity, and that year only four fallas were set up. In 1885 the tax rose to 60 pesetas and only one falla went up in flames. In 1886 the city had no spring festivity whatsoever, after which lively protests were heard. The following year the tax was reduced to 10 pesetas and twenty-one fallas were built.

The first ‘llibret’ was written by Bernat i Baldoví in 1855.

Criticism and burlesque provocation became the keynote of the fallas as they came closer and closer to becoming artforms in the 19th century. Artistic skills began to be exercised to the full. Painters and sculptors were brought in to help. Soon afterwards an entire school of fallas artists began to burgeon, presided over by Antonio Cortina, Andrés Cabrelles and Regino Más. The fallas grew in complexity to become enormous monuments, and an entire industry was born under the auspices of the Guild of Fallas Artists.

The Fallas are a feast to which people from all walks of life can contribute. No one, even if they try, can come to Valencia during this time of year and stay on the sidelines. The catafalques are there in the street. The parades never end, whether the falleros happen to be marching to collect their prizes, offering flowers, coming to the deafening midday sound fireworks sessions, seeing fireworks at night, or listening to outdoor concerts in the streets. Food and drink are everywhere, with typical pastry stands on every corner. The noise is sometimes too much for people used to quieter quarters, but there is no doubt about it. Valencia welcomes everyone with open arms and encourages all to join in the feast.

Tourist Board |

|